︎︎ Felix Petty

On Night

Clubbing

Published in Harper’s Bazaar

I remember exactly the last time I was in a nightclub. It was the very end of Paris Fashion Week, March 2020, the Cicciolina Party at the Folies Pigalle. It happens at the end of every season. Everyone was there. It was all very normal and usual and it should’ve remained a totally unremarkable night out – just another night of fashion week excess – except for the fact that by the end of the month the clubs around Europe would be closed, and this was my last night in a club because they still haven’t opened. I don’t remember much of the music that was playing that night, some hypnotic and swirling techno, and I don’t remember dancing. I don’t remember what I was wearing. I remember trying to summon up some energy to dance. We left early-ish, two in the morning. The kind of time you could only leave a nightclub at when you know there are a thousand more club nights for you to go. The party was still going on when we left. We should’ve stayed.

Looking back at that last Paris Fashion Week now, almost eighteen months later, it’s hard to resist wallowing in the nostalgia for that moment. That season feels quite legendary now, so easy to mythologise. All of it has gained meaning and weight and mystery because of what followed. It was the last dance, the last shows, the last physical interactions, the last time things were the way they always had been.

In the months of lockdown since the two things I’ve missed most may actually be the fashion show and the nightclub. Neither translate very well to the digital environment because both are so physical, so ephemeral and fleeting. They are both full of chance, revelation, beauty, noise, music, lights, boredom, awful people, beautiful people, movement, closeness. They are about chance and fortune and luck and spontaneity. You could meet the love of your life at a fashion show or a nightclub, or hear a song that will change your life, or see a coat that you will buy that will change your life because the love of your life will fall in love with you when you are wearing it. I miss all that.

People talk about old clubs in the way they talk about fashion shows; Margiela SS92 or the Wag Club in 1982 or McQueen SS94 or Shoom in 1991? They are all spoken about in the same hushed, reverential tones: were you there? And the drugs, like the designers, were so much better back then. So much larger than life. They were stronger and bigger and more expensive and more exclusive. It’s all just Proustian rushes of memory now.

Many designers have been playing off that during the months of lockdown, creating moods and feelings and digital shows that exist somewhere between wish-fulfillment, escapism, hedonistic longing for the clubs and nightlife.

Most notable of this was Daniel Lee’s Bottega Veneta show at Berghain in April, which generated some controversy for happening during an intense period of lockdown in Germany, maybe born out of envy as much as anything else. But for Daniel Lee, by staging a fashion show inside maybe the most famous nightclub in the world, he sought some of that club’s magic to sprinkle across his collection, to summon some of that aura.

There have been so few parties to miss over the months lockdown as we have all been digitally invited to everything, but this was a real “were you there?” moment. Something exclusive and unrepeatable, and that’s a feeling that has been partly lost in fashion’s pivot to inclusivity and immediacy. No catwalk pictures were released straight after the Bottega Veneta show. It was still shrouded in mystery months later. What really went on there? All we had to go on were the guests, their outfits, a few blurry leaked images from the afterparty. In that way it mirrored the unknowable interiors of Berghain, which remain a mystery to those who haven’t been initiated.

And this is feeling – of missing the space and aura and glamour of the night club – has been running throughout fashion these last months, from Chanel, who showed at the the legendary Parisian nightclub, Chez Castel, and paid tribute to the multiple generations of chic Parisian leftbank nightlife in the process, to Prada, who looked to the bright primary and neon colours of raving, in a show soundtracked by legendary DJ Richie Hawtin, and which looked to the future, to tactility, reemergence, a new uniform for a new version of real life.

It’s worth noting too that Prada’s new joint Creative Director, Raf Simons, has always explored the hedonistic of nightclubbing in his collections for his namesake label. Anthony Vaccarello at Saint Laurent was another who looked to the glamour of the night this season, he showed chic, sexy, nightlife-ready outfits in the anachronistic location of an Icelandic glacier, but seeing them there, on this rocky and fantastic landscape, just made us more aware of what we are missing in the clubs at the moment. All the clothes we haven’t worn out, that haven’t been seen, haven’t been danced in.

And the menswear shows this June, Virgil Abloh’s Louis Vuitton paid tribute to the Amen Break, the most famous dance music sample, and maybe the most famous sample ever, further exploring the ripples of dance music culture through the world, and the clothes riffed off the styles of jungle and drum ‘n’ bass, and the wardrobe of the ultimate jungle icon Goldie. Dries Van Noten too, opened his collection with the sounds of Primal Scream’s Loaded, and it’s opening declaration of: “We wanna get loaded and we wanna have a good time, we're gonna have a party.” In a collection that looked to the nightlife of Antwerp, his home city.

The world’s of fashion and nightlife have always been intertwined though, and never more than now by their absence. If you were to zoom in and look at the fashion and nightlife history of London, for example, you can see how clearly they’ve influenced and inspired each other over the years, and this inspiration you may find in a city like London or Berlin is totally different to that exhibited by Prada or Chanel or Saint Laurent or Louis Vuitton.

What we see on the catwalk inspired by nightclubs is not necessarily what people wear to go out. Or doesn’t reflect how people actually wear clothes in a club (that is a real club, a dark club, where you are there to dance and listen rather than be seen or photographed) and how those clubs form communities and scenes and how fashion subcultures grow from that, and only then do they end up on the catwalk. And that’s all gone at the moment.

“I think perhaps over the lockdowns of the last year when current designers have been inspired by nightlife it has been more nostalgic, looking further back, they’ve been revisiting punk or acid house and grunge in their collections,” suggests Max Clark, the Senior Fashion Editor of i-D magazine in the UK, when asked about this current moment in fashion. “It’s easier to get a sense of the aesthetics of youth culture now through the internet, and to an extent that’s replaced the experience of going to a club and discovering something new.”

One problem with lockdown life and fashion is that it’s so hard to stumble across something new, in real life. Fashion itself has always been about longing and desire and the endless possibilities offered by tomorrow, and these last few seasons seem to have had a feeling of living for the future, of dressing for reemergence. The longer the pandemic and lockdowns have gone on, the stronger that desire and longing have grown. We miss the scene as much as anything else, the togetherness, the unexpected. This lends the upcoming September season of shows a weight not unlike that of New Look of Dior post-WW2. This is the New Look 2021. The reemergence of the fashion world from the privations of the pandemic. A new opulence? A new hedonism? A new glamour? That’s really what we are looking at for these Prada, Chanel and Saint Laurent shows.

But we’re also looking to something else we are missing from the dancefloor, and that’s how the homemade and DIY fashions of nightlife’s subcultures — from Northern Soul to ravers to disco to house and techno — bleed into the world of the fashion naturally, by osmosis, by the strength of their spirit.

“From the mid-70s Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren's obsession with street culture and youth subcultures led to them inventing and designing the uniform for a style that was so attached to music and nightlife,” Max says, of the history of nightlife and fashion. “They took what was happening on the streets and brought it to the catwalk and that inspired the next generation to look at what teenagers were doing. Ever since then punk, fashion has turned to what was next in youth movements and music, which is intrinsically linked to nightlife, to inform what would happen on the catwalk.”

It’s that cycle of unexpected and revolutionary newness that blossoms on the dancefloors and takes roots across the wider culture, and not just in fashion and music, but in art and cinema.

Take for example Mark Leckey’s seminal piece of video art, Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, which looked to the history of British subculture on the dancefloor, and found a link between Northern Soul and Acid House, to the photography of Wolfgang Tillmans, who documented the sexy and gritty and provocative reality of clubs, the communities that form around music and subcultures and dancing too. Real people rather than the idealised visions of the fashion industry.

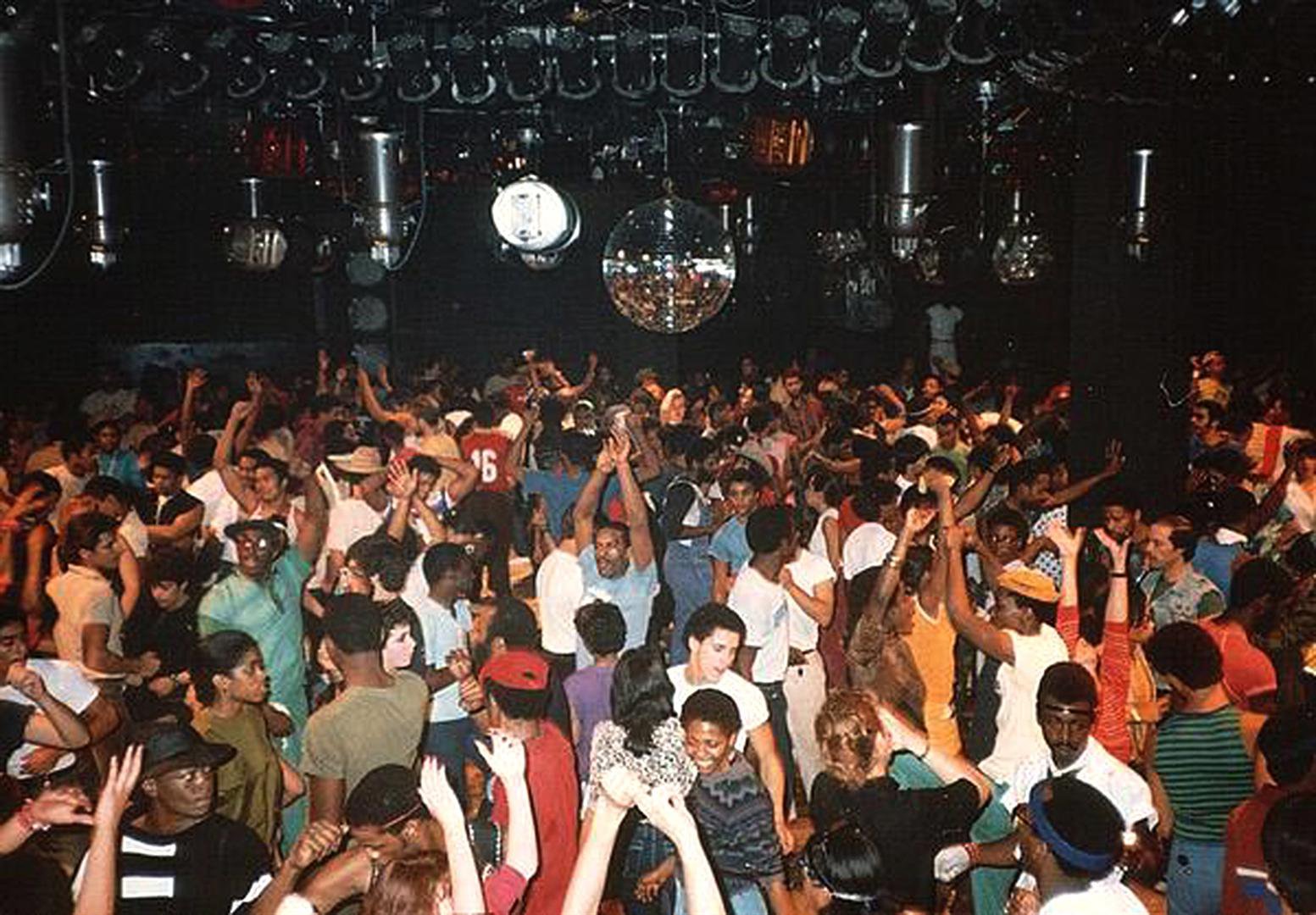

“The inspiration from club kids and high society on fashion is obvious and well documented,” says fashion critic and author Charlie Porter when I asked him why fashion has always so consistently and over so many years looked to nightlife for inspiration. “Less acknowledged are the T-shirts, jeans, sweatshirts, tracksuits worn across the decades at clubs, the kind of thing most people actually wear when they’re going out. I’ve always been more interested in Paradise Garage than Studio 54: a photograph of Larry Levan in a T-shirt and jeans says more to me about how the language of fashion has evolved than anything worn by Steve Rubell.”

“Much of this influence on fashion is subconscious: designers go to the club, they see the people around them, those people are in their mind when they design. Wolfgang Tillmans’s extraordinary work The Cock (Kiss), taken at the legendary London clubnight in 2002, is a really great example of how this messaging from nightlife seeps in: what you see is two guys making out, one in a tracksuit, the other in a T-shirt. They’re having the best night. You want to be there with them. You want to wear their clothes.”

So for all the talk of how the catwalk is looking to the dancefloor as something escapist, it is seeing it the other way round, as Charlie implies, that is most interesting. It is all really about how the scenes and clothes as actually worn on the dancefloor translate into the collections that we find and create newness in fashion. And we don’t have that at the moment. That is what we’re missing.

“The inspiration from club kids and high society on fashion is obvious and well documented. Less acknowledged are the T-shirts, jeans, sweatshirts, tracksuits worn across the decades at clubs, the kind of thing most people actually wear when they’re going out. I’ve always been more interested in Paradise Garage than Studio 54: a photograph of Larry Levan in a T-shirt and jeans says more to me about how the language of fashion has evolved than anything worn by Steve Rubell.”