︎︎ Felix Petty

Constructing

Femininity

and Deconstructing

Masculinity

Published in Harper’s Bazaar

A suit can mean anything. It can be glamorous or it can confer authority. It can be flamboyant, invisible, it is the attire of a movie star or a bank clerk. The suit is about luxury but it can also be egalitarian. It’s about individuality and conformity. All of these things are about power. Or at least an image of power. And invisibility can be as powerful as glamour. The suit can offer you whatever you need. It is the most basic and the most complicated of garments. It is the foundation of all of modern fashion in its ubiquity, in what it stands for or in rebellion against what it stands for. It’s almost blankness is a space for interpretation and possibility.

I envy people who wear a suit with flair because I look – or at least feel – awkward when I’m wearing one, as if I was wearing a costume or pretending to be grown up. Usually my suit wearing is confined to the big rituals; christenings, weddings, funerals. There’s comfort in the appropriate masculine uniform of these ceremonial occasions, and the suit has a weight I’m unable to carry in ordinary life outside of them. It is too heavy. Too masculine. Too middle aged.

I was never a Ted or a Mod. I was never able to turn that weight into something subversive or youthful and subcultural. Few of the people I know regularly wear a suit casually. And yet I have a fascination with this garment, with this weight I can’t carry: with the language it speaks, the rules of it, the grammar of its construction.

Masculinity is constructed, and the wearing of a suit is part of that, but also because masculinity is constructed it can also be deconstructed. The suit too, because all of it’s conceptual attachments are constructed and deconstructed just as easily. Clothes are how we present ourselves to society. You wear a new jacket and it’s unfamiliarity carries you in a new way, you notice yourself again.

The construction of masculinity through fashion is the premise of a new exhibition at the V&A in London, called Fashioning Masculinities. The plurality of the title is important. Masculinity isn’t just one thing. The exhibition takes in everything from Sir Joshua Reynolds’ portrait of Charles Coote, the 1st Early of Beaumont, painted in flowing pink robes and plumed hat and rose ribboned slippers, to a Kim Jones look for Fendi Couture SS21, in which a male model wears an elegant, pistachio-coloured evening dress and cape. It looks to subculture and classical sculpture, Sean Connery and Le Smoking. It shows how masculinity is made through what we wear, but also that the idea of what masculinity is, is itself is totally in flux and constantly being negotiated. It places fashion in the context of the time too, fashion is not an end in itself but an intrinsic part of history.

“Our opening look is by designer Craig Green, which is so sculptural, so poetic, so beautifully represents our interest in bringing together art and fashion to explore how menswear has been and still is a powerful tool to perpetuate and challenge definitions of masculinity,” says Rosalind McKever, one of the curators of the V&A exhibition, when I ask her what she thinks the most important garment in the exhibition is. “The elements of this ensemble come from traditional garments that can be found in any wardrobe: their rearrangement though speaks of fluidity and plurality, and envisions a multitude of identities that can be explored through dress.” The Craig Green look that opens the exhibition takes general codes of masculine dress as a form of status— it is part samurai, part business suit — and literally tears them into pieces, reassembling them into a sculpture floating above the wearer, almost surpassing the concerns of the body. It is an attempt to free it from not just the general codes of masculine dress, but also what those codes entail in everyday life, the shapes they force you into.

The V&A explores those shapes across three sections, titled Undressed, Overdressed, and Redressed, the curatorial team explain. In Undressed it explores, “the fashionable body, which since the 18th century has emulated classical, sculptural ideals; in Overdressed we step into the elite masculine wardrobe full of ornamentation, colour and luxurious fabrics, and bring together the riches of 17th and 18th century fashion with the 1960s peacock revolution and contemporary boldness; and in then in Redressed, we look at how the suit has been constructed since Beau Brummell in early 19th Century London, how it became the epitome of timeless masculine elegance from the 1930s, and appropriated as symbol of resistance and sensuality by Marlene Dietrich and Yves Saint Laurent; and then in recent decades, picked apart at the seams by designers from Tom Ford to Rick Owens, Raf Simons to Jonathan Anderson. The exhibition takes fashion, such a sensitive barometer to societal change, as a lens to look at the shifting modes for expressing and performing masculinity through dress.”

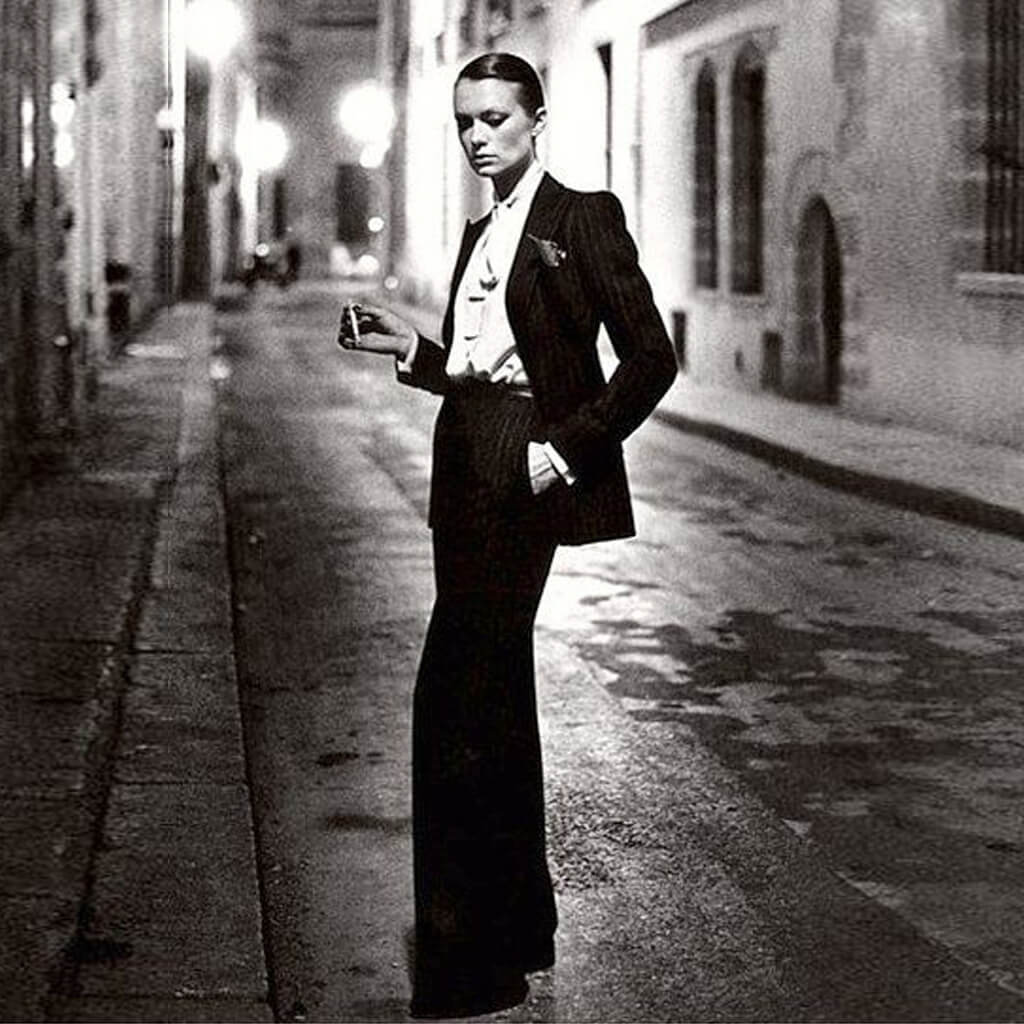

Does the feminine in suiting and tailoring only exist in relationship to masculinity? If we liberate masculinity from the suit, what does a woman in a suit present to the world? It’s certain Le Smoking, Yves Saint Laurent’s 1966 two piece women’s tuxedo, wouldn’t haven’t maintained such a hold over the imagination if it wasn’t as much for what it destroyed as what it created. The men’s suit is ancient, almost outside of history, but for women it more or less starts here. Yves once said that fashion was about “communicating the art of living” and what Le Smoking proposes is modernity, modern life. All the greatest couturiers not only reflect but shape the time they are working in, and Yves was maybe the most impactful.

“I think it’s the ultimate in sharpness,” Osman Ahmed, Fashion Features Director of i-D magazine explains. “Putting on a perfectly tailored suit feels like a second skin, an armour for the modern world. It feels proactive, like you’re making a conscious decision to step out into the world with an intention: for some, it’s to do business; for others, it’s to convey power; for many women, it’s to subvert what it means to be ‘feminine’. For example, Le Smoking is and will always be the last word in sharp, sexy elegance.

But before Le Smoking, though, there was Dior’s New Look of 1947, and specifically the Bar Suit. The Bar Suit and Le Smoking are almost a yin-yang. The Bar is not sharp like Le Smoking, but an accentuated vision of femininity; a white satin jacket with soft shoulders and a dramatically nipped-in waist and a decadent flowering expanse of black skirt radiating outward. It’s a silhouette that seems to embody and define elegance, or a certain kind of elegance, a vision of Post-War Paris. Le Smoking is androgynous as much as feminine. It is sexy in a completely different way; blunt, confrontational, tough.

Le Smoking was released in Yves’s 1966 Haute Couture collection but it most famous from a 1975 Helmut Newton image. In the photograph an androgynous women stands in an obscure Parisian alleway, jacket open, wearing a perfect white shirt and cravat, smoking a cigarette. Her hair slicked in a parting that could’ve come from the Golden Age of Hollywood. She’s timeless. There’s a hint of melancholy to the image too, sadness at the impossibility of this glamorous chimera really existing. Helmut’s photograph offers something completely different to that which was originally presented by Yves on the catwalk nine years earlier. It took this new image to transform Le Smoking into some iconography.

If a suit offers an image of power to a certain kind of masculinity, it can also be used to undermine that power, or to subvert it towards the new kinds of feminism that emerged post-war. And what both the Bar Suit and Le Smoking seem to promise is liberation. The feminine dress, historically, of a certain kind of Western women, involved complication, fussiness, constrictive layers. As a very obvious example, we could look to Coco Chanel’s elevation of trousers as a staple of women’s dressing in the 30s, as a different kind of freedom, the ease of dress so long offered to men.

To an extent all gender roles are constantly both being enforced and constantly being subverted. We can return to that Fendi couture look, for example, and look at that wider collection, which was inspired by Virgina Woolf’s novel Orlando, whose protagonist glides through the ages of history as both a man and a woman, undermining the codes that support both as individual entities.

Virginia Woolf was in part inspired by the fact that, contemporaneous to Orlando, was the fashion in the 30s for Lesbian women to dress in very traditional masculine clothes. This is specifically referenced in the V&A exhibition in the form of poet and author Radclyffe Hall, who wore an older version of a very masculine smoking jacket, she had short cropped hair, a bow tie.

In Orlando, the titular character moves from Elizabethan England, where the young nobleman is a favourite of the Queen and in love with a visiting Russian Princess, to Constantinople, where Orlando miraculously transforms into a woman. Orlando lives out the next centuries first with a band of Romani gypsies and then back to England, where she lives as both a woman and a man, evading marriage proposals and eventually publishing a work of fiction that has been centuries in the writing.

In many ways the novel is a cornerstone of a very radical kind of liberation for women, that was partly indebted to the liberation offered them by fashion: Orlando, as a woman, often finds herself constricted by feminine dressing. But it also looks to another history, where men were freer in their dress too, where flamboyance was vaunted as a form of masculinity. Orlando is about how in flux all these relationships are; masculinity and femininity, freedom and flamboyance, expression and domination.

These are issues many designers have tackled over the years. One most interestingly, is Rei Kawakubo, who at Comme des Garcons has been able to create a vision of womenswear free of the limitations of the body itself, but also of the history of fashion, and is instead reaching toward some pure form of expression.

But her menswear roots itself in the history of menswear and of the way men dress, the uniforms that are created for them and worn by them. In the V&A exhibition there’s a look from Rei’s SS20 Homme Plus collection that seems to, all at once, exist in the future, past and present; it is part Renaissance and part Punk. The model wears a crumpled velvet jacket with a pink and white striped shirt underneath that falls and hangs long like a skirt beneath the jacket and is ruffled at the collar. The model wears pearls and trainers and tights and their hair falls in early adolescent waves. It is, like Orlando, a vision of beauty, almost without gender. Or at least it is not defined by it. The suit jacket and shirt are offered as subversive, freeing statements; gender is only interesting in how you can free yourself from it.

Or maybe in how you can confront it: a modern analogue to Radclyffe Hall’s masculine pose, from a very different angle, could be Kim Kardashian in the latest Balenciaga campaign. Kim is a vision of constructed, unashamedly femine, sexual, commodifiable, womanhood. But in this Balenciaga campaign she is clouded and accentuated by a long black coat. The coat’s silhouette is one of Balenciaga designer Demna Gvasalia’s trademarks at the house, quite square and boxy and exaggerated in the shoulder, pitched forward, nipped in impossibly at the waist, with high, padded hips. It’s a formal business coat twisted into strange proportions, at once both liberating the body and reminding us all of that world famous body underneath.

Demna Gvasalia once said: “How do you persuade a woman to wear a two-piece suit who is not the German Chancellor?” Which seems to be one problem of the idea of tailoring for women, or indeed modern tailoring in general, in the imagination. For all the liberation it seems to offer, the suit and tailoring are stuck, probably unfairly, in the imagination as dull at times. Historically there is much to discuss in the role of tailoring in liberating women from the constrictions of dress, but how do you persuade women to wear two piece suits, which can so easily devolve into dullness.

Max Pearmain, a stylist and editor, who works with the likes of Chanel and Chloé, as well as countless fashion magazines, disagrees though. “Perversely I’d argue it’s the conservatism of the suit that allows it to feel consistently relevant, timeless and potentially even almost provocative,” he says, when asked about the suit as a modern fashion item. “The expectation of fashion is often to be ‘a challenge’ but that idea feels lightweight in comparison to the intelligence a suit can suggest. The volume at which a lot of visual and creative stimulus is spoken at feels increasingly loud within the now, whereas to me, an important piece of tailoring can feel like a seductively private conversation, and that energy feels clear and modern in my mind. We’re supposed to be reducing and refining our consumption. Buy a suit. Wear a suit.”

To an extent that need for liberation has been achieved. A taboo can only be broken once. It’s no longer shocking or new to see a woman in a tuxedo, even if it can still be incredibly chic. Radicalness, like masculinity and femininity, are relative. David Bowie and Annie Lennox both wore suits, both looked androgynous, both shocked, but they approached this from totally different angles. But, as Max suggests, there’s modernity too, to be found in the blank spaces of the suit.

Osman agrees. “Arguably, suits are the backbone of fashion,” he says, “And ultimately, a suit is a blank canvas for experimentation because it’s more traditional associations with formal dress codes, school uniforms and corporate environments make it deliciously ripe for reinvention and subversion. Designers can’t resist the magnetic pull of it, and they’re always thinking up ways to make suits feel better-suited for the future. I have a blazer from Comme des Garçons that is cut like a Medieval suit of armour, a pinstriped one from Armani that could have been cut in the 1920s, a latex-collared Chanel bouclé blazer, a great big slouchy one with the widest trousers you’ve ever seen from Yohji. None of them are your typical run-of-the-mill two-pieces, and yet are just as easy to wear, as familiar as the clothes I wore to school.”

Liberation, has, to a certain, been achieved. But there is still something paradoxically rebellious and provocative in the suit and in tailoring because its so anachronous to modern life in so many ways. We live in an age defined by streetwear, ease, branding, mediocrity, and the suit and tailoring is anathema to that. I’ve never daydreamed about a £1000 logo hoodie. The hoodies are daydream about have a lived in cosiness and comfort, they aren’t defined by their expense or branding but something else that is much deeper. And yet, when I see someone wearing a fantastic suit in a film, it could be Alain Delon or David Hemmings or Marcello Mastroianni, it is still about dreaming, which is a kind of liberation too, the possibility of reinvention, becoming someone else, not defined by who you were or society even, but about who you could become.