︎︎ Felix Petty

Body Language:

On Dancehall Aesthetics

Published in Kaleidoscope

In the last decades Dancehall has splintered and fused into pop music in the US, blending into the prevailing mainstream sounds of hip-hop, trap, and R&B, and leading the latest generation of dancehall stars from Jamaica around the world.

Dancehall definitively emerged with Wayne Smith’s “Sleng Teng” in 1985, made with a present sample from a Casiotone MT-40 keyboard; with its shuddering, rhythmic, digitized beat full of hypnotic swagger, it used the nascent technology to propel Jamaican culture forward: brashly modernist and futuristic, it was a reaction against the conservative political culture of the island at the time—and a reaction, too, to the more holistic energy of roots reggae.

Proudly working-class, dancehall spread

to England’s clubs, becoming ragga, but also sowing the seeds of what would become grime a decade later, another genre full of male braggadocio, female swagger, sound clashes, toasting, high energy rhythms, and lyrics exploring the self-made glamour, excess, and hardness of urban life.

But dancehall also became an international pop lingua franca, the music of Rihanna and Drake

and US arena tours. It has maintained its resolute Jamaicanness even in its diasporic reflections,

full of sex, extravaganzas of female style, and a cacophony of fashion and sound as a form of utopian self-reinvention, dance as a form of profane religion. Dancehall, most importantly, turns history upside down. Instead of colonized subjects, dancehall is the story of Jamaica imposing its culture on the world.

Jamaican writer and academic Carolyn Cooper and Anglo-Jamaican curator Carol Tulloch discuss the interweaving of the dancehall story across the two countries over the last 30 years, tracing the homegrown and diasporic evolutions of the music, style, and culture that has defined Jamaica’s recent cultural history.

“That Jamaican people, instead of now being the colonized subjects, are the colonizers. And we have turned history upside down by imposing Jamaican culture on Britain.”

Felix Petty:

Dancehall and Jamaican style is a very big and broad subject, so we probably won't be able to cover half of the things we'd like to. But I guess we can start speaking and see where we end up and where we go. I wanted focus not so much just on the music but on the style, the context, the culture—and I guess also, with both of you, the relationship between Jamaica and England and these different currents of influence going back and forth between the two countries, the two various scenes and styles and patterns of influence as well.

Carol Tulloch:

Well, Carolyn is the expert in all of this.

Carolyn Cooper:

We’re all just dabbling, Carol. I'm not an expert on fashion; you have the theory of fashion in its social context.

FP:

The easiest place to start I think is with the emergence of dancehall in Jamaica and the context it came from, what it was a reaction against, what it was for, and what was happening in Jamaica at the time.

CC:

I would say that Jamaica dancehall culture emerged with the moment that technology entered the music scene. Sleng Teng Riddim is conceived as the first defining moment, when dancehall rhythms emerged in Jamaica, electronically generated by a synthesizer. For some people, dancehall is a whole spectrum of dance music produced in Jamaica, but we also know that dancehall is this particular mode, where the rhythm seems to become dominant and it really expresses the vibrancy of a youth culture that emerged in the late 70s, which was a time of political upheaval in Jamaica. Dancehall was a challenge to the existing norms, standards of propriety, and so on. It was a mood of rebellion and resistance.

One of the ironies of the emergence of dancehall is that the conservatives in culture kept saying that dancehall was such a break with the high cultural values of reggae, because dancehall tended to focus on sensuality and violence, and they conveniently forget that, in the early days of reggae, that is exactly how reggae was dismissed. Reggae was called vulgar, was the music of the inner city, too; it was not respectable.

So one generation's vulgarity becomes the next generation's culture. And already I feel that we're seeing dancehall come of age in this manner.

Another important thing to note is that there's going to be always new variations of Jamaican music emerging, and morphing, particularly in relation to Britain. Grime, for an example, could be seen as a variant of dancehall.

FP:

Very much so. It’s interesting the way it becomes more than just music—the style, the lyrics, the cultural context, the way the form morphs into other forms.

CC:

Yes. It's a music; it's a politics; it's a fashion. And that style was really seen as a contestation of good taste. I think in every hospital in Jamaica there's a sign saying that dancehall dress is prohibited. And I wrote an article called “Emergency Undress,” for a book Carol did, where I made the point that, if a parent is coming to the hospital in an emergency and what she's wearing is her dancehall clothes, I really don't see how it can be appropriate for the hospital administration to tell her that you can't wear a dancehall dress. And they say that it's about health, but it's just nonsense. It's really a rejection of working-class style. Because dancehall style is predominantly working-class, although, with people like Rihanna and their adoption of dancehall, it’s became a global cultural signifier. But dancehall has emerged from the Jamaican inner city. That’s its context.

FP:

Maybe we could talk a bit about what that style is specifically.

CC:

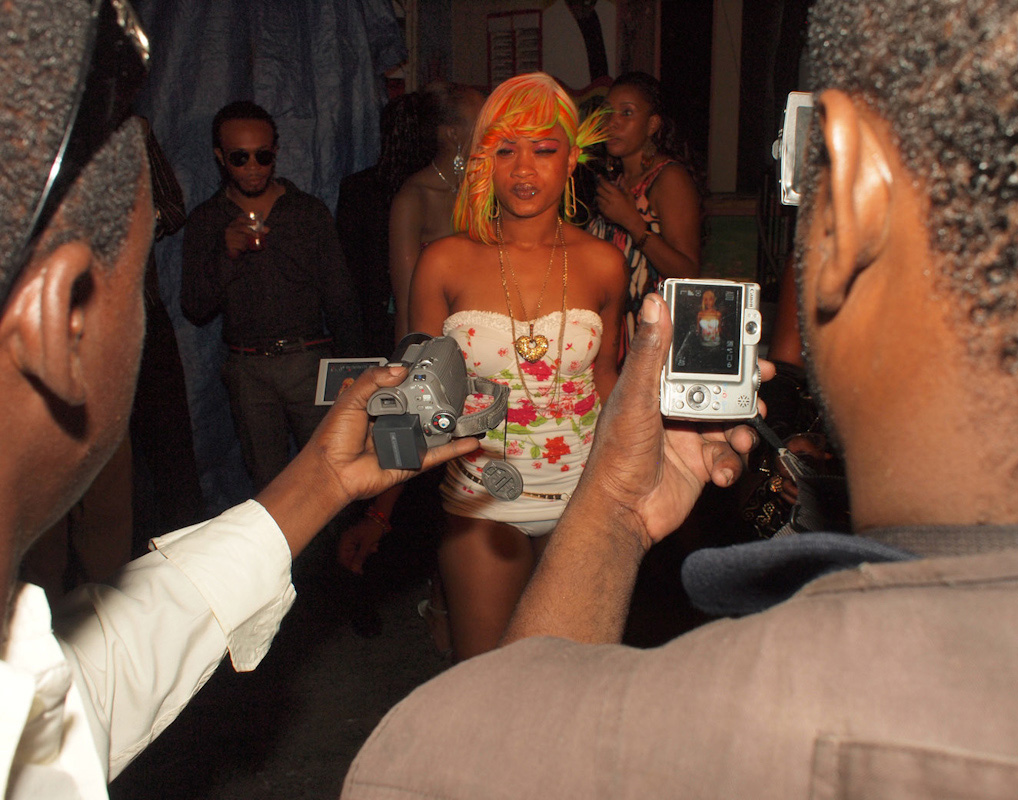

All right, let me give you a classic example. Which is Carlene, the original dancehall queen, and this image of her at Reggae Sunfest 30 years ago. As you can see, her rear end is completely exposed with this mesh which is pretending to be a garment. This is a picture that appeared in The Sunday Gleaner newspaper, the height of respectability—legacy media. They published this photo with the heading, “Peek-A-Boo,” and then this is the description under the photo: “Carlene, leader of the dancehall models, was caught backstage at Reggae Sunfest last week. As is the norm, her revealing fashion was a showstopper.”

And that is the first thing we can say about dancehall style: it's a showstopper; it's revealing. We know about the batty riders, those very short shorts. I saw Lady Saw recently, and she was wearing a lovely outfit in which her midriff is barely covered—again by mesh—with the top of her breasts showing. It is style associated with sensuality, carnality, with exposing the body, and celebrating the body.

The way in which the female body is represented in dancehall could be seen as a continuation of West African female fertility rituals. And you can also say that the Western anxiety about the body—all of those Victorian notions of respectability—are being challenged by an Afro-centered spirituality—what I call “embodied,” because the body and the spirit are organically connected. Spirituality is not about something immaterial. You manifest spirituality in the body. And that is why, in many traditional religions, dancing is such an important ritual. It is through dance that the spirit powers possess people. You dance your way into your spiritual understanding. I would also like to make the point that the pelvic gyrations that dancehall culture is famous for have their genesis in religious dance in Jamaica.

They have a movement in Kumina—which is a traditional Jamaican religion—where the male and the female come together and they hit each other's pelvis. That is the same thing as dancehall; the only difference is dress. In traditional religious performance, the body is covered: the women wear floor-length skirts and so on. In dancehall, they wear these batty riders, and so the pelvic movements get exaggerated because of the lack of clothing. So the context is everything. One is religious, one is secular; one is sacred, one is vulgar, but it's the same movement. And if you are willing to set aside some of your, let's call it prejudices, your prejudgments, you'll be able to see that this is a continuity of bodily forms, and dancehall is really a contemporary manifestation of traditional African religions that have evolved across the diaspora.

And, in fact, I was really fascinated with one of my friends and colleagues, professor Murray Warren Lewis, who talked about going to Guyana and seeing women performing a female fertility ritual. And they were crying out, and one of the things that they were saying was “bumba,” and “bumba” in Jamaica is a bad word, a reference to the female pubic area. So when I heard that, as I say, I'm absolutely right, “bumba” is spiritual. This also got reinforcement from an argument from Peter Tosh of all persons. I did a wonderful interview with him and he talked about the hypocrisy of the Jamaican elite and he said, "If I said, 'Damn you, fuck...' Nobody will say anything. But as soon as I say bomboclaat, people get vexed." And he said that the reason why people get mad is that the word "bumba" has too much spirituality in it.

But, also, these are not just curse words, these are words that are mobile. They express a range of emotions. If you win a lottery ticket, you will say, "Bomboclaat." That is not a curse; it’s joy. So the way in which we use bad words, for me, is a sign of the way in which spirituality and quote unquote "carnality" are organically connected in African diasporic culture. And I think it comes from the continent of Africa, where this Western divide between the sacred and the secular does not exist. I keep making the point: it's a continuum.

CT:

Well, interestingly, that image that Carolyn showed of Carlene—I remembered the first “Street Style” exhibition from the V&A—it would’ve been 94 or 95—and there was a section on jungle and ragga—ragga being the British expression of dancehall. I don't know if you can see this okay, but this image is of a woman in chaps, and then it's all net underneath so you can see her bottom.

CC:

Yeah. Oh, same aesthetic.

CT:

And that's 1994. And you were saying that—

CC:

Yes, and Carlene's was 1993.

CT:

And this other image, here, it’s black satin and tulle bra with gold metal buttons and decoration: gold metal jewelry, quilted satin, zipped chaps, stretched tulle shorts that are see-through. It’s on a woman called Pascal. She's a designer. And she said, "We wanted a kind of cowboy look, so we made the chaps and carried the dancehall style through with gold buttons. Girls were wearing things like Wonderbras, so we decided to make it in a Chanel-style quilted fabric with a bustier top. I'd wear it with a pair of black shorts, but a lot of girls would wear it with just a G-string under the netting.”

I remember when I was doing my postgraduate certificate in education to do teaching—this was kind of 1990, 92—ragga was really just taking over, well, England, but in London, specifically. I was living in Hackney then and I was teaching in Newham. And there was this guy called Danny Edwards, who was a mature and older student. I'd say he was in his 30s, doing fashion design. And I remember he’d be wearing a white denim shirt, denim jeans. But they're completely ripped up—I think they used to call them "gunshot" trousers because you'd have the holes in it and leather boots.

And Danny wore these garments as an outfit in 1992. I mean, he used to shave his eyebrows with lines going through them. The haircut was cropped at the back and higher on the top. He acquired the shirt from his uncle's shop Stars in Dalston in 1984. The jeans were by Exhaust, a favorite label of ragamuffins, and were bought whilst he was in Kingston in Jamaica in 1992. The boots came from Camden Town Market.

So this was really the style in the UK at that time. Or this young woman called Chirone Wiltshire, and it's an outfit that she wore to the Notting Hill Carnival and we photographed, and we actually had this image in the “Black Style” exhibition. So she's got on a bra, a pink vest, and then the short shorts.

When she saw the image again, years after it was taken, when we met up so we could borrow the outfit for the exhibition, she said she hadn't realized how daring the look was at the time. It’s a look that she wanted to wear to Notting Hill Carnival. But she said she's now worried about what her dad's going to say because he's a practicing Rasta. And what will he think about her outfit? But she still lent it to us for the exhibition, which was amazing.

It was interesting that you spoke first, Carolyn, and talked about the batty riders and some of the clothing being more revealing, body conscious. And it's the same thing that was happening in Britain.

CC:

Same thing.

CT:

And it’s the same thing, in a way, with the men. You would have guys wearing shirts that would have lace on the back so it was more revealing. So blurring the lines of what is masculine, what is feminine.

But then going to Jamaica, I do remember going to Spanish Town, and I think it was my nephew who told me about a guy who had a stall there that would sell clothes, CDs, tapes. The guy at the stall, he was incredible. Because all his hair was twisted—I wouldn't say it was—and he had gold jewelry hanging through his hair. He was dressed all in black. And the smile he gave me, I'll never forget. His mouth, a mouth of gold. I had never seen it before. It was incredible.

And it was actually very different from the UK. Because I lived just down the road from Dalston Market. So, for me, it was part of the aesthetic of our area. Do you know what I mean? It was part and parcel of all the different range of looks that you could see in that part of East London.

The last time I was in Jamaica was in 2017. And I was quite surprised that my eldest sister, who is in the church, was wearing clothes that were super body conscious, with that celebration of the body and the wearing of clothing that follows the body line regardless of the shape.

To me, that means it had become part of the mainstream. I think it was something really interesting that Carolyn said about how one generation defines a particular musical style or dress style and then the next generation. So when Carolyn was saying that reggae was seen as vulgar, well, even at one point they saw ska as vulgar because of the dance styles.

Then it becomes accepted by another generation, perhaps because of the way that it's taken on across the world by different groups—and the cultural value.

Those images I mentioned were both exhibited at the Victoria and Albert Museum. So, what I'm saying is that it was a testament to the cultural value of ragga as part of Black British style. Then it's part of Black British culture, and Black culture in Britain. Then it's connecting with Jamaica.

And there was a review I remember, of the exhibition, and the journalist went in and he said it was worth the entry fee alone to see batty riders at the V&A. He never thought he'd see the day.

CC:

The empire is falling; it's falling! Poor Miss Vicky must have been so distressed, rolling in her grave.

CT:

And the other thing I was going to say is that... I think Carolyn was referring to seeing grime as a legacy, a continuation of ragga. And in the sense of, with grime, there is that whole thing. It's part of storytelling, which, for me, dancehall is part of that. For me, the clothing just is a kind of storytelling too about life in Jamaica or the States or in Britain.

CC:

I just wanted to reference a poem by the distinguished Jamaican poet Louise Bennett, called “Colonization in Reverse,” which deals exactly with what you have been talking about with the journalist going into the V&A and seeing batty riders.

She says, we turning history upside down. That Jamaican people, instead of now being the colonized subjects, are the colonizers. And we have turned history upside down by imposing Jamaican culture on Britain.

CT:

Exactly. Exactly. Sometimes it's not even consciously. On the tube in London coming back from Rose Sinclair's exhibition on Althea McNish, I saw a young Black woman get on the tube and I couldn't take my eyes off her. Because, basically, it was like all the images that she had in her bedroom that represented Blackness, she wore on her body. I can't even explain it. It was so amazing.

CC:

Did she allow you to take a picture?

CT:

Somehow, I didn't even want to take a photo. You know, you live in London, you live in England, you live all over the world, you've seen images, images, and images. But I've not seen anything like that for a long time, an image like that.

CC:

Tell us a bit about it. Tell us about it.

CT:

So her hair was beautifully slicked tight and into a tight bun. Of course she had lots of gold jewelry, big jewelry. Then she had these Ladette baggy trousers, like cargo pants with the tight pockets. The trainers, I can remember, were red and black. She had a vest on, her big earphones. Her makeup was meticulous. She was probably in her late teens, but she’d pulled all the references, all these different kinds of cultural references that she might have had on her wall—that's how I viewed it. And you couldn't help but look, because she was carrying it all. And for me, with dancehall, and particularly because I'm getting a broader sense of dancehall, a lot of the women there were doing the same thing, pulling all these various references together. And I always think of that photograph. Let me see if I can find it; it was in the Black Style book and it accompanied Carolyn's chapter.

When we did the words on [Akeem Smith’s exhibition] “No Gyal Can Test,” I realized that the space where those looks were created are as important as the looks; it’s all these things that contribute to what dancehall is. So this is the image here. So that's Akeem's aunt.

CC:

Yes.

CT:

There's a bit of footage on Instagram, where he’s speaking to her about the exhibition and archive and all this, and she’s totally lost for words, because what they did wasn’t worthy of being archived; it was undervalued.

CC :

I quoted her in the chapter of Sound Clash when I looked at [the films] Dancehall Queen and Babymother. Because I found a lovely statement by her. And she says, with dancehall, the outfit is like a disguise: it frees you to become somebody else.

CT:

It’s clothing as a form of freedom. It is the outfits as a disguise, a form of self-invention.

CC:

Yes. That is it. Sandra Lee actually said something like: “I can be somebody; I can be somebody different tomorrow.” And there’s another quote I like too: “In the dancehall world of make-believe, old roles can be contested and new identities assumed. Indeed, the elaborate styling of both hair and clothes is a permissive expression of the pleasures of disguise."

CT:

You know what, Carolyn? You reading that quote from Sandra Lee, it just makes me think about—and I say this in quotation mark—about "professionals" or "leaders" of organizations and their obsession with having a uniform so that they look the same every single day.

CC:

Wonderful point.

CT:

But I've always thought: But what about your own expression? Dancehall is about “creating,” so you can express yourself in different ways at different times and things.

So that point that you've just read that Sandra Lee says, that tomorrow they can be someone different, they've got all those same references for dancehall aesthetic. But within those different references are those different elements, tools, accessories, garments.

Akeem said that [his aunt Paula] Ouch would also be a kind of actor’s consultant when they were creating the look. That is what some artists here would call the "right to performance," to be who you want to be, how you feel on that particular day.

CC:

Uniform signifies uniformity, and it doesn't allow any kind of aesthetic variation from the norm.

It's the same problem we have with schools in Jamaica and the school uniform and regulating hair: not allowing dreadlocks in school, because dreadlocks are going to harbor lice, and the boys can't have a mohawk.

And as I keep saying when I write about this: you want young men in particular to feel as though they can express their identity. This is how their creativity is being nourished. But the school system doesn't want that. It just tries to erase this difference.

And so, it alienates young men. Why should it matter if I want to come to school with a mohawk? How is my mohawk going to stop me from learning?

FP:

Is it true also then that dancehall is a space—we talked about the women of dancehall, but also for men within the scene—is this a place where dressing up, this kind of self-expression in a society where this is not often seen as the most traditionally masculine thing, where it can come out?

CC:

Men do dress up. And the men move around in crews, even though these are not homosexual crews. They are homosocial. You know that distinction? It's men going out in a crowd, and many of them are part of the entourage of an artist and stuff. Men dressing up in dancehall is an issue of style too. So the men do dress up, but the women are the ones who are the bearers of the style.

I invited Vybz Kartel to give a talk at the university, much to the dismay of the administration. But more than 5,000 people showed up. The university had never had any event like that before with so many people. One of my colleagues told me that for all the time he has been teaching at the University of the West Indies, this is the first time his child asked if he could come to anything at the university.

During his talk, he spoke about bleaching his skin. And he said he did it for his tattoos, so he could use his skin as a canvas; he said bleaching has nothing to do with low self-esteem or anything like that. It's about creating this artistic space for him to be able to now add these layers of tattoos. I think tattooing is one of the main ways in which men in dancehall decorate the body.

CT:

I'm going to come back to that thing of brilliance, where you were talking about what's happening with school uniforms and you're raising difference, and whereas, with dancehall, it's that exploration of possibilities of how different you can change your body. There's some that are wearing corsets, and then they have spikes sticking out of the side of these corsets and all of that.

And it was really weird—I had completely forgotten, and I might be going right out on a limb here, but this photograph, I found it in an antique shop. I’ve never seen women in Jamaica dressed that way. They're beautifully dressed; they'd gone to market, and the photograph is from 1895. But for a long time, we couldn’t work out when the photograph was taken.

Because all the clothing referenced different eras, times. They’d kind of patchwork things together—a sleeve, a bodice, a skirt—all from different eras. And that's what I was saying about with dancehall taking references of things that they like, that they're into, that creates the look that they want to achieve. And that's what had happened. And this is late 19th century. So that thing of creating your own look, creating your own possibility of who you can be, was as far back as then. For me, dancehall is just like a continuation.

CC:

Absolutely brilliant, Carol. And even though, when we talk about the African continent and people selling their precious artwork for baubles and this kind of thing, the baubles were new decorative objects that they were able to now incorporate into traditional designs. I think we need to recognize that eclecticism is an essential element of the African aesthetic. And when I say the African aesthetic, I don't mean to put there's only one African aesthetic. It's African aesthetics, plural. And, in our context, sometimes it's poverty that forces people to be creative. That we have an expression, you turn your hand, make fashion; you use your hand to create fashion. And it means that you may not have everything that you need, but you just have to use what you have to create what you want. So there's that sense that not having what you need becomes a motivator for creativity.

CT:

You've just reminded me about a phrase that my mum used: “Every mistake is a fashion.”

CC:

Yes. And I think of the verb “to fashion” as in “to create.”

So fashion as design for clothing is one thing, but this whole idea of fashioning yourself, creating yourself, you're creating images that are now going to articulate who you are. So we need to look at dress as language and that language as, what does your dress say about who you are? And dancehall dress says, “Me don't care what they think of me.” I don't care what they think about me; here I am. Just take me—take it or leave it.

That's the essence of dancehall. I remember one of my friends going to the screening of a dancehall movie, and he said he saw a woman whose dress was resisting exposure. The dress was so—it was so impossible for the dress to cover her, but you can't tell her that she isn’t sexy. Her dress may be resisting exposure, but she was not, she was just exposing. The dress was really a fig leaf. Her dress was a figment of her imagination. It was how she imagined herself. And you know, you see these woman with these tight clothes, and they know that they're sexy. You cannot tell them that they're not sexy. They know they are sexy. Sex is in the eye of the beholder, but sex is also in the head of the beholden.

CT:

Girl, you know what? It’s quite interesting, because one of the things I'm always talking about is that thing of distance with my parents coming over in the 1950s and meeting in England. But that thing of respectability, it was heightened. So when you were sent out of doors, you had to look the best you could. Do not have your hair in dreadlocks, because you're not going to be accepted. If your hair isn't pressed and neat and tidy, somehow you're not going to treated well in a shop. Everything is done to be accepted, really. But always, or a lot of the time, this is at the expense of who you really are, who you want to be.

CC:

Absolutely. Disguise again. Disguise yourself to pass.

CT:

Exactly. And I think there is a courage there in saying, “This is who I want to be. This is what I want to wear. I'm going to do it.”

CC:

It's revolutionary reclamation of identity. In a society that tries to tell you your chat bad, because the body language of dancehall is also the language of Jamaica. The Jamaican language and the Jamaican language is bad; you mustn't speak that way. It's a sign of the lack of intelligence. Everything negative and people's body language in dancehall is Jamaican body language.

“You've just reminded me about a phrase that my mum used: ‘Every mistake is a fashion.’”